Language plays a hugely important role in shaping our perceptions of nature and influencing our human-nature relationship. It can promote a growing kinship … and yet also deepen our separation and othering of nature. Welcome to Regen Notes.

We have not always struggled to understand our relationship with nature, indeed until relatively recently it has ‘just been’. In the context of biophilia, it is our recent effort to label what has always been innate, and of no need for classification. (See Regen Notes - Growth from Words)

Ancient Greek philosophers like Plato and Aristotle emphasized the interconnectedness of humanity and nature. Plato, in Timaeus, described the cosmos as a living organism, with the human soul originating from a universal soul present in all living things. Aristotle, in Physics, suggested that humans are distinct from other animals due to our ability to reason, but we also share many characteristics with the natural world.

The Romantic Movement in the 18th and 19th centuries further developed the idea of humans as part of nature. Romantic poets like Wordsworth, Coleridge and Shelley celebrated the beauty and power of the natural world, whislt philosophers like Rousseau advocated for a return to a simpler, more natural way of life.

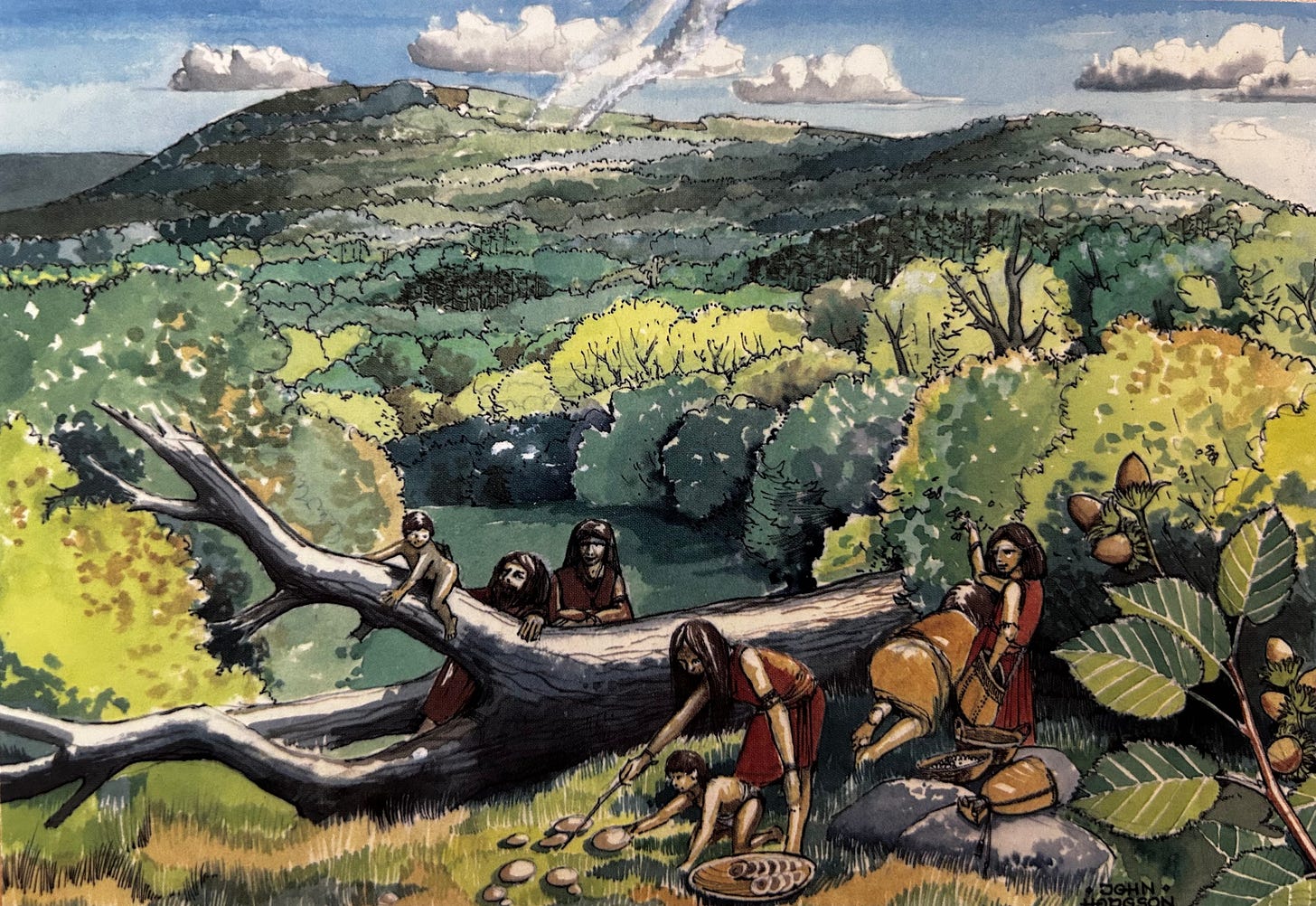

Indigenous cultures around the world have traditionally held deep respect for nature and a sense of kinship with all living things. Many indigenous worldviews view the natural world as a sacred and interconnected whole, with humans as integral members of this community. For beliefs and cultures that see the natural world as ancestors, and that in a future life may well be another natural entity, the concept of connectivity is profound.

Robert Macfarlane’s wonderful book Landmarks, about land and language, documents myriad place names of great particularity that illuminate a real ancient Anglo-Saxon intimacy with the land and her beings.

Language can be a powerful tool for fostering a sense of kinship with nature by providing a common vocabulary and shared understanding of the natural world. It allows us to articulate and communicate our relationship with the beauty, wonder, and interconnectedness of ecosystems. Gaelic place names in Scotland can be so poetic and descriptive of place and the natural environment.

It is through language, that we share stories and experiences that connect us to nature, deepening our understanding of its diverse forms and the profound impact it has on our lives. It allows us to communicate our concerns about environmental threats and inspire collective action to protect the planet’s rich biodiversity.

Yet language can also perpetuate a sense of ‘othering’, distancing us from nature by portraying it as something separate from human experience. This stems from anthropocentric language that emphasises our dominance and control over the natural world.

The use of metaphors that depict nature as a resource to be exploited or a force to be tamed can reinforce the idea that humans are superior to the natural world. This can lead to a disregard for the intrinsic value of nature and a lack of empathy for its well-being.

Ki and Kin ...

The wonderful Robin Wall Kimmerer suggests the pronouns of Ki and Kin ...

“With full recognition and celebration of its Potawatomi roots, might we hear a new pronoun at the beginning of the word, from the “aaki” part that means land? Ki signifies a being of the living earth. Not he or she, but ki. So that when the robin warbles on a summer morning, we can say, “Ki is singing up the sun.” Ki runs through the branches on squirrel feet, ki howls at the moon, ki’s branches sway in the pine-scented breeze, all alive in our language as in our world.

We’ll need a plural form, of course, to speak of these many beings with whom we share the planet. We don’t need to borrow from Potawatomi since—lo and behold—we already have the perfect English word for them: kin”

When we reference a 1000-year-old tree as “it” it is with an arrogant perspective, yet by using “ki” we start to understand the character of the tree and a forest of kin.

How would our relationship, our kinship, with nature be different if we were to view our built environment and urban landscaping as a community of kin? And to refer to the plants we bring into our buildings as biophilic elements as ki? (Shifting from “the plant needs attention” to “ki needs attention”)

‘Ecopsychologists have suggested that our conceptions of self as inherently separate from the natural world have negative outcomes on the well-being of humans and ecosystems. Perhaps these words can be medicine for them both, so that every time we speak of the living world we breathe out respect and inhale kinship, turning the very atmosphere into a medium of relatedness’.

“If pronouns can kindle empathy, I want to shower the world with their sound” Robin Wall Kimmerer

“As hunter-gatherers, those who were most attuned to the natural environment were the most likely to survive. But then we built all this infrastructure. We are trying to use the hunter-gatherer brain to live in the highly stressful and demanding modern world.” Dr David Strayer, a cognitive neuroscientist who heads the Applied Cognition Laboratory at the University of Utah. The nature cure: how time outdoors transforms our memory, imagination and logic

Biophilic Society Locus Call

We are seeking passionate people on biophilia, biophilic design, regenerative design, regenerative economy, nature and nature based solutions, willing to support our reconnection with the natural world, forming The Biophilic Society Locus (BSL) that will ensure the rigour of our approach and support the The Biophilic Society evolution. The call is open until the 22nd December

The Biophilic Society ‘Locus’ will be our focal point where (nature / biophilia / regenerative) principles and influences can converge, interact and emanate from. It will act as a kind of guiding vision or north star for biophilia and nature connectivity.

As in nature, a Locus enables self-renewing to function more like living systems, with a clear sense of shared purpose and aligned activities centered on regenerative concepts.

Zoom Regenerative 61

Regenerative Design at Ramboll – 3 Principles in Union

Looking forward to round off 2023 with a regenerative design focus with Veronika Petrova sharing insights from Ramboll’s Regenerative Design journey.

Over the last 12 months, on the back of the COP15 in Montreal, the theme of exploring nature-positive has been central to Zoom Regeneratives. Nature as a Partner is one of Ramboll’s three Regenerative Design Principles that Ramboll considers in union with Future Generations and Everything as a Nutrient

Zoom Regenerative 60 in Novemeber was a wonderful exploration of living well with Justin Eade sharing insights from his work at Glimpse.

Nature Positive at COP28

It is encouraging to see nature positive activity at COP28 admist the heavier newsworthy ‘phase out / phase down’ fossil fuel debates.

“And working with nature, truly working with nature, we will find that she can do much of the decarbonisation heavy lifting for us in the built environment” My comment at COP27 Egypt, this time last year in our LFE session for the UN Climate Change programme.

Nature day at COP28 is on Dec 9th - follow news and comment from the brilliant Nature4Climate newsletters.

More Chief Nature Officers

Lombard Odier see nature is an investment conviction, being the first bank to appoint a Chief Nature Officer, a role that we believe will become essential across all sectors as we transition to a net-zero, nature-positive economy. (See earlier Regen Note How to give nature a voice)